The Ais People

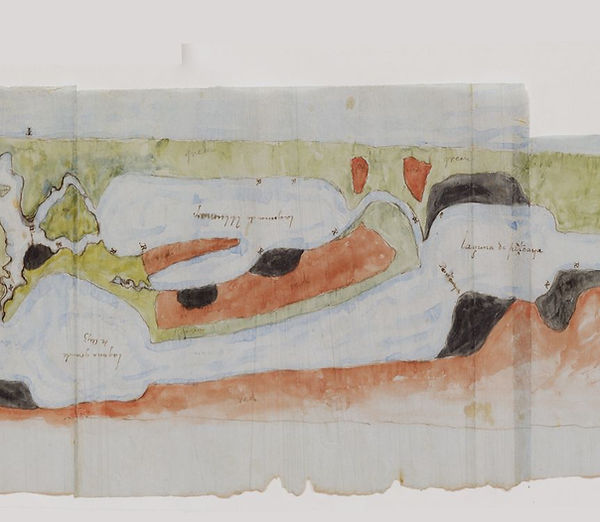

In 1605, Álvaro Mexiá was tasked by the Spanish government to attempt peace with La Florida’s native population, specifically the Ais people. As a result, the Ais territory was mapped by Álvaro and he wrote letters describing his experiences and observations. This is the first time El Río de Ais was mapped. When Florida became a U.S. territory in 1822, the river was renamed the Indian River.

El Rio de Ais Map

The Ais and the Spanish colonists were not friends, but they did trade and barter. Despite the relationship, skirmishes did occur. If the Ais were ambivalent about the Spanish, they truly disliked the English. Accounts from 1696 tell of an English shipwreck around Hobe Sound. Although the English shipwreck survivors felt threatened and at times were mistreated, the Ais ensured the English arrived safely to St. Augustine into Spanish hands. The Ais would bring shipwreck victims to St. Augustine to collect a ransom. They were also renowned divers, selling or trading Spanish shipwreck items back to the Spanish!

8BR1936 (Florida Master Site File) on the Banana River Lagoon in the city of Cape Canaveral was occupied by the Ais Indians and is probably the winter town of Savochequeya, an Ais village documented and mapped in 1605 by Spanish explorer Álvaro Mexiá. Carbon 14 (c14) dating showed the bottom of the midden to be c 1500 AD and the bottom of the midden c 1700 AD. The midden was a coquina clam midden. In all, about 60 Phase 1 shovel-tests were conducted, as well as one 1 x 2 meter trench, along with four 1 x 1 meter trenches. A salvage trench to accommodate an electrical line was also dug, 35 meters x 50cm wide.

"AVT" by Rick Piper

The community-participation excavation that uncovered the remains of Savochequeya took place from 2015 to 2019 and was led by archaeologist Alan Brech and board members, Rick Piper and Brent Russell, of the nonprofit Ais Village Trail organization. With the support from their board of directors and the work of local community volunteers, this multi-year dig helped document an important part of Brevard’s native past for posterity.

Material culture on site includes bone pins, bone and shell beads, shell tools, charcoal, pottery sherds, and bones associated with food ways. A surprise was the total lack of drilled sharks’ teeth, leaving the group to wonder if they had been replaced by European goods. Three early glass beads were recovered, as well as a possible Tamboc button. This style of button is flat, with a copper alloy wire shank inserted into the mold and produced from the late 17th c into the 18th c. Shell tools appeared with less frequency than pre-Contact sites. European iron from shipwrecks and lead splatter were heavily used on this site. Although there are plenty of St. Johns pottery sherds on site, there are no olive jar fragments – reports say the Ais did not have a high opinion of the pottery.

Button

Glass Bead

Shell Pin

In Florida's wet climate and sandy soils prehistoric wooden structures quickly deteriorate; but the rotted wood leaves stains in the soil called post molds. By plotting the post molds, archaeologists can recreate the outline of buildings that make up a village. Numerous high-definition post molds are abundant on the site. Found on the site was evidence of several pits and fire hearths.

Post Mold

200 years of Spanish rule (1513-1821), with a brief interim of 20 years of British rule (1763-1784), resulted in neither assimilation nor destruction for Florida’s native population. Many of the Christianized natives were moved to either Cuba or Puerto Rico when Spain left. The remaining Florida natives were either absorbed into other kingdoms or had been killed, died of disease, or captured and sold as slaves. After 1760, the Ais people disappeared from the historical record.

"Florida's Lost Tribes" by Theodore Morris

Recommended Reading:

"A Hundred Giants: The French Huguenot Experiencein Florida: 1562-1565", by Gaëtan Algoet, T.L. Armstrong, and Dr. Robert H. Baer

"God’s Protecting Providence; Being the Narrative of a Journey from Port Royal in Jamaica to Philadelphia, August 23, 1696 to April 1, 1697", by Jonathan Dickinson

“Jonathan Dickinson’s Journal or God’s Protecting Providence, An Early American Castaway Narrative,” edited by Amy Turner Bushnell and Jason Daniels, with a contribution by Jeral T. Milanich

"Florida’s Indians from Ancient Times to the Present," by Dr. Jerald T. Milanich

"Discovering Florida: First-Contact Narratives from Spanish Expeditions Along the Lower Gulf Coast", by John Worth

.webp)